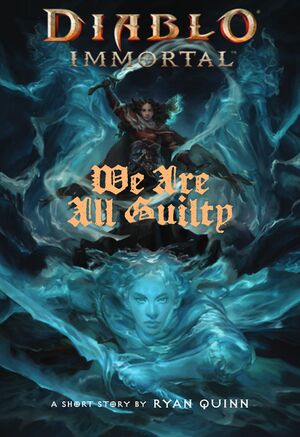

Мы все виновны

Мы все виновны (англ. We Are All Guilty) — рассказ Райана Куинна, опубликованный 21 мая 2024 года.

| “ | Пронизывающие ветра, клубящиеся ледяные туманы, угрюмый корабль — ерунда по сравнению с пережитыми мучениями. Кез носит на душе бремя воспоминаний о погибших друзьях и утраченном доме. Однажды отказавшись повиноваться своему народу, теперь она вынуждена искупать этот «грех». Но кроме бури-недоучки Кез, команде не на кого рассчитывать. Сумеет ли она вспомнить свое обучение и защитить корабль от нечисти из туманов? И захочет ли?..

|

„ |

| — Описание рассказа с официального сайта Blizzard[1] |

- Автор: Райан Куинн

- Иллюстрации: Синтия Шеппард

- Редактор: Хлоя Фрабони

- Дизайн: Кори Питершмидт

- Консультанты по истории вселенной: Иэн Ланда-Биверс

- Творческие консультанты: Мак Смит, Дэвид Ломели, Джон Мюллер, Рафал Прасжлавек, Дэвид Родригес

- Публикация: Брианна Мессина, Карлос Рента, Эмбер Пру-Тибодо

- Особая благодарность Скотт Бёрджесс, Тодд Кастильо, Цянь Линь Лью, Джесс Литтон, Джастин Мюррей, Эмиль Салим, Хантер Шульц, Бен Вагнер, Майк Яклин, и разработчикам команды Diablo Immortal — нынешним и бывшим — за приток свежей крови в Санктуарий!

Рассказ

When they marched Kez out of her cell and onto the barge, silence harried her more than two years in a cage. Nobody shoved, spat, or flung rotted fish or words twice as spoilt. Guards in wide saw-scale helmets slow-walked her up the slippery plank, one hand each on her shoulders, steady but gentle as the good rain.

It had been different last time. Last time she deserved it.

But today they needed her, she figured. So there was respect, or what little of it these lampreys could fake. If she was lucky, they’d let her eat with her hands instead of chin-down in a bowl.

The end of her atonement was so overdue, Kez was surprised anyone had bothered. Maybe her accuser was dead. Maybe they were just going for a swim. She didn’t let herself hope it was anything more than a break in the storm.

Kez stepped around the square turquoise sail and onto the back bench of the barge her escort appointed her to.

It was a gray day, which meant dripping rain and numb faces, but no hail. Kez filled her lungs with icy, bracing air. There were figures lumped all over the back bench and down in the rows, breath preceding them in the cold, a few peering over when she came aboard. A motley of pales and tans, talls and shorts, made uniform in haphazardly stitched brown prisoners’ clothes.

Their arms were covered, but they had no furs; some shivered and huddled together like she’d done with the neighbors back home when it got too cold to be alone. Home was Rag Sound, westernmost of the Cold Isles, one of the many tiny islets surrounding the capital of Pelghain. Tiny islets draped in a skirt of flotsam from the city’s ports, always last to hear of a crisis until the waves dropped it on top of them. Home was Rag Sound before home was the cage.

One of the prisoners, a thick-neck with a pig’s nose and retreating black hair, was coughing and moving his throat like he’d swallowed a squid. But he paused at the sight of Kez, snorted up something, shook his head, and looked over at the guards.

“Just lovely. Anyone else you need me to carry on my back? A baby, perhaps?”

He hacked a couple more times. Kez took him for a hunter, maybe—she could see him out in the swells with a horn and a spear to feed his family. Nobody special. Probably sent to the cage after a fistfight in view of the wrong people.

Kez knew what he saw when he looked back at her.

Dusky skin, dark hair so unkempt it flew free of her hood and billowed in the wind even wet. Wiry, but shorter than most. Hands at her sides, her feet pointed away from each other as if she was preparing to jump. The cage hadn’t taken that from her—couldn’t—even when there wasn’t room to stand. Her prison clothes were frayed; the neck and hems looked like rats had been at them.

Kez did not cough or shiver much in the cold. Only her lip wriggled like a thing clinging to life. Her brows pinched together. She could show this thick-neck he was wrong, could take him to the ground and let the other scabs laugh at him. He was here for atonement, after all.

But that wouldn’t get her home.

Instead, she tried to remember what she could of the training. Imagined herself in the middle of a ring of people, all whispering and shouting at her, all wanting things she couldn’t possibly give them, contradictory things. A storm of distractions. Needs that were beyond her. Needs she had to let go. She listened to them scream until it sounded like a hum.

The furrows in Kez’s brow eased. She relaxed her lips until they were a straight line, betraying nothing. Her face became a mask of simple placidity. Calm was just another prison, but she needed to pretend. Even so, Kez tapped her manacled wrists on the rail of the barge. She couldn’t help it. Two years. Two shit years. She’d been shut away long enough to waste all that promise the sages had talked about. But she didn’t say a thing aloud in rebuttal. Just tapped and listened to the hunter cough until he glanced away.

Then she heard the squeak of boots coming up the plank. Solid boots, not sealskin. An officious stride, in perfect step with others. Wind howled in her ears— just hers; the sails of the barge lay utterly still. Her throat closed of its own accord.

Three guards banged their spear hafts on the deck. One intoned, “Sage Kynon,” and each of the others repeated it in turn, matching their volume.

Kez flexed her hands, doing her best not to look at him.

Kynon was dressed imperially, in the style of old Pelghain. A pair of dyed redand-purple wool mantles crisscrossed his shoulders, held together by a golden clasp of two scepters. Thick hair unspooled around his throat and shoulders, though he kept a trim beard.

His mouth was tranquil and downturned, his eyes gray and—coupled with the frown—pathetic.

The look of a functionary. An empty vessel. Only his station demanded attention.

Even with her hands manacled, Kez was sure she could charge him and knock them both off the barge. Maybe he’d gash his head on the plank as he fell. Maybe the maarozhi—sea beasts—would be on him before he could swim back.

Her constant companion since the training—the ring of voices from her mind and her heart, which sounded like her and her old friends and a hundred ancient whispers she hadn’t named—burbled for calm. Wind is not cut, they said. Waves are not stopped. Find tranquility in the heart of the storm, and such tranquility endures its passing.

She shut them out. She couldn’t even feign calm, hearing the mists whisper to her like this.

Kynon paced in front of the back bench. One of the prisoners, a gangly sort with sopping brown hair, sat up straighter as the sage’s eyes passed over him. Kynon ignored him and spoke, cheeks puffing like a fish.

“Mehrwen’s Stay is an islet of little import or travel. This week it is drowned in the mists.”

Kez knew the Stay. A half day’s sail from Rag Sound. Named for—supposedly—serving as a onetime retreat for Mehrwen, the moralizing and dour empress of old. The mists, most of the sages insisted, were Mehrwen’s last breath, when she swam away from her murderous sister to die somewhere people could still find and praise her.

The sage continued. “We were able to evacuate most of the people. Not all. If any who remained behind rose as fiends, they must be put to rest. Else, when the winds shift . . . they will journey upon them.” Straight through Rag Sound and the rest of the isles to slaughter folk, if history was any indication.

Kynon read the prisoners’ names and numbers, one at a time. Ponnyd, Cedrouk, Silla. All from the same isle.

“Gart, from Rag Sound. One year of atonement. One year remaining.” The hunter with the pig nose hacked in answer.

“Only one?” someone else whispered, incredulous.

Gart smirked.

Kynon ignored them. “Paltik, from Rag Sound. Four months of atonement. One year remaining.” Paltik was the one who’d sat straight up when Kynon looked at him. He saluted at Kynon’s back as the sage paced.

“Kez, from Rag Sound,” he said, with no more or less emotion than the others.

“Two years of atonement. Two years remaining.”

“Yes,” was all she said.

“Though you have failed in your duty to your station, Pelghain does not see your flaws today. Only your promise.” He sounded tired, like he’d given this speech before.

“Your atonement is no longer to hold yourself apart, but to try again.” He gestured to all of them, though his gaze remained on her. “To honor your guilt and to prove that your souls have been changed by it. You do this in two days’ time, and I will annul your sentence. You will be free to dwell in any of the refuge isles as will have you.”

Two days. Then home. It sunk in deep.

Kynon paused, plainly for effect. “Should you fail and somehow survive, you will return to your cages and hide your shame from the sky.”

Kez decided not to tackle him. No one got off the boat.

Gart’s coughing eased over the journey, as they closed in on the islet of Mehrwen’s Stay. The barge, big enough to seat the sage’s entire retinue, needed a lot of hands, and Kynon ordered the prisoners’ manacles removed so they could row. After he marched out of sight, Kez wondered, not for the first time, if they might revolt. Take over the barge and sail for . . . somewhere else. It would have to be well beyond the storms. And farther than any of them had sailed in their lives.

But she understood the allure of atonement after all these years. Two days and a bit of dark work, and they’d all be home. And she knew the spines of people like Paltik, with his fast salutes—they didn’t know how to refuse an opportunity. They were from Rag Sound. Most of them had never known opportunity of any kind.

The mists were settling in around them, sticking like ice-white cobwebs to the barge’s netting, placed to keep out sleet but worthless against the murk. Near the prow, someone was blasting a sounding horn on a steady cadence. When the mists fell, it was easier to collide with quiet things.

A few of the Rag Sounders had jostled together to get oars and push the barge for the first leg of the journey. As the day lengthened, their pace slowed until Kynon signaled for the guards to row the rest of the way.

The Sounders were rude clay, but Gart at least seemed like he’d been in a fight. Kez shifted over to where he was speaking with Paltik and cleared her throat.

“Did the sage or guards say how many to expect? Anything about the land? What weapons they brought for us?”

Gart laughed out loud. “You giving orders now?”

Kez knew his type. There was only one authority in his world, so she appealed. “No. I’m trying to make sure we get out of this alive.”

He stood up, steady despite the ground wobbling. Gart was tall—the kind who loomed simply by being near. He cracked his knuckles; it sounded like he did it often.

He didn’t have a weapon on him. Not that she could see. But he had reach, and his fists were free after too long bound up. Kez tried to keep her placidity in place as he sneered down at her. “Don’t play at telling me what to do, girl.”

Calm was not helping, but Kez didn’t want to hurt their slim chances. She struggled to tamp down her irritation. “I’ve been to the Spiral and back. You’re lucky I’m telling you what to do.”

Gart smiled at that, all gap teeth, his hog face taking on a manic cast as he stepped closer to her and spread his arms wide. The message was clear: You’re just talking. Come on. Take a swing. If the guards could see them squaring up, they paid them no mind.

Kez couldn’t throw Gart off the barge. He’d freeze to death. So she rose to a standing position, pointed a fist at him, and yanked back her other arm for a body blow. Gart tensed, raised his guard—and she kicked him right in the yoke.

It was a cheap shot, a Rag Sound special. Hazardous and familiar. Small chaos followed, with gangly Paltik struggling to hold back the other prisoners, a few ready to fling her off the barge and most laughing so hard they forgot they were cold.

Though the veins in Gart’s neck bulged out, once he regained his composure he started laughing too. Kez held her hands up to show she was done. She kept her voice loud enough for the Sounders to hear, if not the sage’s people.

“Kynon doesn’t tell us anything because he doesn’t care if people from Rag Sound live or die. But I do. And I can get us home.”

Gart was deathly quiet, so Kez kept on.

“I promise. On the Sound.”

Gart stood, hocked something over the side of the barge, and held his hands up. Smiling different now. Listening to her at last.

Kez, Gart, and Paltik eased their way over to the front of the barge, stepping carefully as patches of fog drifted down all around them. Two from Kynon’s retinue flanked him for protection; another sat on a massive trunk, occasionally blowing a horn to signal their way through the mist. The sage was looking intently past the prow, but he turned swiftly when Kez spoke up.

“How many are there?”

Kynon was grim. “We evacuated all but two families. There should be no more than eight souls left on land.”

They were six prisoners in total, by Kez’s count. Ponnyd, Cedrouk, Silla, Paltik, Gart, and herself. She stepped closer to Kynon, careful not to enter what his guards might consider threatening range.

“Where are your Tempests?”

He cocked an eyebrow at that. It wasn’t the question he’d expected from her, of all people.

“They are needed at Pelghain. You are the closest thing to a Tempest in reach of Mehrwen’s Stay,” he said flatly.

Gart scoffed, heedless of what it meant to question a sage’s words. “She’s really a Tempest?” He looked at her with disbelief and something new. Fear? Admiration?

Kez started to say that she would be by now, but Kynon slashed her protests to pieces. “She was in training. And she is lucky to carry Mehrwen’s burdens still.”

She had finished most of the training. Had drifted across icy lakes alone, drinking the mists in, minutes at a time, for years. Had learned the blade dance, slain maarozhi, had even paid the cost to command the wind and waves, to become a vessel for the wisdom of Pelghain’s past. She’d inherited a lifetime of incessant words in her mind, centuries of recollection in a thousand different voices.

Irritability had always come easily to Kez—but the mists, the constant soft buzz of their whispers, made it worse. Calm was her nation’s highest pursuit for good reason.

Her status was not up for discussion. Not with him. “What’s in the trunk?”

The guard with the horn dutifully hopped off the trunk and flipped it open.

“Spears for all of you. Some sturdy leathers.”

“And?” Kez waited for more, and when she didn’t hear it, she kept up. “Where’s my sword?”

Kynon sighed. “It will be useless to you.”

So he had it. Had he brought it to remind her of her failure?

Anger at a sage was serious; loud anger was punishable. Kez tried to form the right words, to entreat him. But all that came out was her pain.

“That’s years of my life, you cawing shit.”

Kynon’s fish cheeks bulged. He raised both his arms, and his retinue stepped forward. The guard with the horn looked like she might grab Kez, but Kez tensed her hands into fists and bent her knees.

Paltik jabbed Kez in the kidneys as he stepped between them. His meaning was clear: If one of us makes trouble, all of us go in the water. A lackey’s way.

“Sage Kynon, please, I beg you listen. She forgets herself . . . but she speaks for each of our atonements.” Paltik pointed at himself with a soft palm, pointed at Kez, the guards, the other prisoners, the sage. “Please. We are all guilty.”

Kez hated that phrase. It was commonplace in every corner of the Cold Isles, no matter how far from Pelghain. It meant, “Remember that everyone makes mistakes,” but also “Everyone is responsible for everyone else’s mistakes.” The worst kind of cowardice—spreading out the blame for something you did, until there was so little left nobody could see it. It led the weak to leadership, forgave the unforgivable . . . and it played favorites. Kynon’s guilt—the sages’ guilt—belonged to every soul in the Cold Isles, but Kez’s anger was her problem. No matter how right it felt.

Paltik’s words worked for Sage Kynon, though. Of course. He shook his head. “Have it, then.”

The guards opened the trunk and dug around while he continued. “I will return tomorrow at sunset. Do not address me until you have proof the fiends’ numbers are thinned. With at least one slain for each of you, or your atonement will continue.”

As the others slipped on boiled leathers, a guard placed Kez’s sword in her hands, and she fought back a sigh. She remembered when its sawteeth broke. Nobody had bothered to fix it. At least the metal was polished enough to reflect her face.

A wind edge was supposed to be precious, a blade that let Tempests harness the fury of the northern gales against Pelghain’s enemies. This one’s hilt was years from a fitting. It was an old, pitted thing, in the worst shape it had ever been.

But not useless. Not to her.

They hopped off the barge at the flattest part of a rocky brown expanse, ringed with drifting crusts of ice large enough to raft on. A dell split the islet’s hills down the middle, where the mists would be thickest, and six prisoners trudged toward it with Kez in the lead.

Kynon had told Gart—because he refused to address Kez directly—that he would not wait near the mists for their work to be done. He was needed elsewhere, or so he claimed. And he asked that those unequal to the task wait on the shore for his return, rather than risk being killed and rising as mistfiends, worsening the threat.

They were warmer, at least. Kynon had given them furs, great dense cloaks of stinking, matted sheep’s wool, and pouches of dried mushrooms. The sage had taken a passing interest in their success. But that didn’t mean he needed them all to come back.

They paused for air at the side of the dell, the sound of their boots cracking gravel an odd substitute for the islet’s absent birds and insects.

Through the valley’s entrance, they could see white mist pouring upward from the ground like freezing breath. Clumps floated by their company, solid enough that Kez sidestepped to avoid touching them, and she urged the others to do the same. She’d seen untrained folk take in too much of the mists—gasping for air like they’d fallen into freezing water, their skin ice cold, suffocating before they rose as fiends. When the wind died and the brushing of the waves against stone faded into the distance, the mists writhed even still.

The contingent held their spears in a muddle of stances, some ahead with their elbows locked, some tight in at their sides. Kez wrinkled her nose at that. Maybe half of them had brought spears on a hunt. At most.

Paltik had his hands choked up on a spear when Kez tapped him on the shoulder and adjusted his grip. “You need enough room that you can stab something without getting your fingers near it.”

“You should go in front, Paltik,” Gart broke in, shaking his head at the display. “A man of the empire knows what he’s good for.”

Kez rounded on him. “Stop acting like you’re the only one here. If any of us die, the fiends’ numbers grow. Simple enough for you to see the problem?”

Gart just snickered. At least he’d shut up. Paltik was certainly ashamed, but she caught him shifting his grip as they walked, taking practice jabs at the air.

It wasn’t much. But it was something, and she had promised on Rag Sound itself to protect them. So she plodded on, looking back and forth between the path and the blade of her sole sword, checking her reflection every few minutes to see that the mists hadn’t entirely closed around her group.

The people of Mehrwen’s Stay would have built their houses high up, out of the dell, to avoid flooding. Kez reasoned that the Sounders might climb the valley’s ridge and search for their quarry in their former homes. She led the prisoners upslope in wide arcs, zigzagging away from the valley walls whenever they grew fog laden, testing piles of loose gravel herself before urging the others forward.

She had hoped the mists would be thinner as they ascended, but nearly an hour in, Cedrouk and Silla were starting at sounds Kez missed, jerking their heads around painfully fast and mumbling to themselves. A sure sign.

Kez piped up, precise with instructions but silent on the consequences. “I’m going to talk, and I’m not going to stop until we get somewhere clearer. I want you to listen to my voice and ignore everything else you hear.”

No one argued as she drove them steeply uphill, yammering about the Sound, about ice walks on the flats and the last good bowl of sattlefin and mushroom she could remember before atonement, and even things she didn’t like talking about, like missing her friends back home.

“Shircan and I used to go ice walking out on the flats in summer. I don’t think she wanted to be a Tempest. But when you see parts of your home breaking off and floating away . . .”

You have to do something. She didn’t say it, but Paltik nodded anyway.

“We begged the sages to teach us the blade dance. We lay out on the ice, told them every pure and dark thing in our hearts. I thought by the third day they would say we weren’t good enough and send us home. But they didn’t. They judged us fair back then. I practiced for months until they let us row out to the Spiral. It took years before our first sip of the mists. We . . .”

She trailed off. She had to stay calm. Had to focus.

“You was doing what, before all that?” Gart asked, huffing along.

“Just scavving. Trying to keep the roof on.” Nothing special.

“Oh yeah? Me too,” he said.

“Same,” Paltik said.

When she ran out of things to talk about, Kez started to repeat the prayers of purification, of calm, of legacy—three at a time, just saying them aloud, not thinking about what they meant.

Power uncontrolled is the doom of the soul.

To live in the sight of others is to change.

Great works rinse small rancor.

Paltik repeated them with her, and some of the others took them up, though they still shot uneasy glances around. Halfway up the side of the dell, the mists wrapped around clumps of snowy rock, pointing up and out like a jumble of fingers.

They were fine until they weren’t. Kez checked her reflection again, and she couldn’t even see herself for all the shrouding. She held up a hand to halt them.

The others looked terrified. Kez had trained in places like this one, but she’d started with minutes at a time. Even full-fledged Tempests wouldn’t chance mists like this, dense sheer walls pushing down on them from above.

The ridge wouldn’t work.

If there was somewhere to hide deeper in the dell, down at the valley bottom, maybe her call could still reach their quarry. It was no longer raining, after all. The winds were calm. If they stayed that way, maybe the mists wouldn’t settle on top of them.

That was it. If they could find a stream within a few minutes, they’d have cover, water, and an obstacle. If not, they would double back, take a long walk around, and try the ridge from the opposite side. Looking at Paltik’s halting gait and Gart’s manic glances around, Kez felt her choice making itself. She spoke loudly.

“I’m going to stop talking, and we’re going to move fast. The only thing you need to listen for is the sound of a stream or a river. We find flowing water, and we head upstream.”

No longer mouthy, Gart jogged to the front of the pack, jutting his head out to squint in the fog. “I got good ears. Let me take the lead.”

She’d figured Gart for a hunter; he seemed like he knew what he was doing, so she didn’t object. And the others ran behind him, heads swiveling as Kez did her best to listen for moving water and ignore the half-formed whispers creeping at her ears.

Power uncontrolled is the doom of the soul.

And then:

Power gripped tight is the doom of the world.

They scurried quickly down the hill, lungs sore from half breaths. As the valley flattened out and their trail started to wind, they kept a tight line behind Gart, stone silent, making sure none could be lost to the mists.

Gart stopped so short Kez almost ran into him. His shoulders were squared, and he was staring at something she couldn’t see. Kez tensed, backed up a couple steps, moving her sword in front of her body as he turned—

And he was chuckling, standing a few dozen feet from a sluggish, half-frozen turquoise stream, empty of fish and plants. The water crawled over angular rocks a few feet deep, but Kez could see it widening further off, perhaps a minute’s run from the valley wall. It might work.

Her sigh of relief frosted out, and similar gusts followed from the other silhouettes around her. Their features were hard to see, even as they fanned out and came nearer. She counted. Five others. All the prisoners were here.

“The people who died will come for us if we make ourselves known,” Kez explained. “I’m going to use this stream and call just one of them.”

She continued. “Some look like they did when they were alive. But they’re not people anymore. They’re fiends of the mists. They’ll take your breath and your skin if you let them.”

Paltik’s face twisted in horror, and Kez reflexively put a finger to her lips. Gart, uncharacteristically quiet, asked if she’d ever killed any.

“Not yet,” she said. “But I’ve seen them die.”

“That why you only have the one sword?” Gart asked, snickering at his own joke. Tempests bore two, as a matter of both pride and pragmatism.

Kez was learning to ignore his barbs.

She looked at Paltik. “Listen to me. We can make it out of here, and then that sage won’t have any hold over us ever again.”

“How do you know?” He sounded tentative. On the brink of something.

“I promised,” she said, with more heat than she’d wanted, but repeating herself was a waste of breath. “I promised on the Sound, didn’t I?”

He didn’t say anything, just looked at her, so she pushed on. “We can ambush them, and we can kill them. One at a time, if we’re careful. You just need to do exactly what I say.”

No one protested, so Kez told them everything she knew about what would happen next.

“To reach them, I need this water to flow,” Kez said, gesturing at the ice-clogged stream, “as fast as possible.”

Rag Sound did not boast the elevated cave networks of Old Pinnacle or the mighty seawalls of Stormbrace. But everyone on the Sound knew how to scavenge, how to break things down, though it did no good to the legacy of imperial Pelghain. So the prisoners found heavy, oblong stones in a matter of minutes, brought them in a hurried line, and hurled them into the stream to shatter the ice.

Kez held her sword in a reverse grip, the blade curving along her arm, and weaved it like she was painting. The air was her palette and canvas. Mist drifted around the edge in thin, unnatural ribbons. The prisoners looked to her in formation, and she spoke her best wisdom to them.

“They’re drawn to our breath. Take a deep one. Don’t breathe in any of the mist. When I say, Gart and Paltik, push out everything in your lungs. The rest of you, hold it. Keep your spears at hand. It’ll happen fast.”

As her contingent sucked in air, Kez rolled up her sleeve and ran the ragged edge of her sword across her underarm. It bit painfully, but she got what she needed. A dozen drops of blood, barely visible, fell into the icy stream. She watched the water flow, pointing her stained sword at it, willing to dead Mehrwen that it would be fast enough.

And it was. Ice cracked as the wind whipped where Kez’s blade aimed, the stream surging forth, carrying her blood to the heart of the Stay.

“Now.”

Gart and Paltik expelled frosty breath into the air. Seconds later, as if in response, a solitary keening answered, a canine snarl delivered as a human scream. Closer than anyone expected. Kez’s call had worked too well.

They barely had time to scoop up their spears as the mists washed over them like a tide.

Kez twisted, trying to keep her eyes in the present as phantoms from her past reached for her mind.

Soldiers yelled for their families as they waited to die. Sage Kynon shouted at them to keep fighting. Somehow, she could hear each voice, clear over the impossibly loud crashing of the ocean. It was violent, not today’s calm. And those people weren’t her comrades. Weren’t these comrades.

Everything in the mists was unmoored in time. They held memory inside and craved more, and Kez was out of practice at keeping them back.

So she bit her cheek, hard enough to make it bleed, and held tightly to her sword and swung. She found herself in the present again, mist rushing around her feet and billowing over her eyes like a wet blindfold.

Kez spun in a circle, commanding the wind to carry the mists away, and they did as she bade, whirling back from her outstretched sword. She couldn’t disperse all the mists, but maybe she could hold them at bay.

In the ringing clouds, she looked for the others, but saw only two forms come into focus: Paltik and the shadow devouring him.

The mistfiend had been a girl about half Kez’s age not long ago. Death in the mists had dyed its loose braids the color of old moss. Its skin was etiolated and its eyes gaunt, with nails longer than fingers. Its jaw was stretched stiff in anguish, and its eyes were empty as a corpse’s. The mist was its puppeteer.

Kez had told Paltik, had told all of them, not to attack before the fiend was fully manifest. But his spear lay on the ground, and the mistfiend’s cold fingers were clamped around his wrist and throat.

Kez couldn’t keep the mists back and strike at it. But as long as it held a living being, it was briefly form and flesh. And Paltik, bless him, was screaming loud enough for everyone to hear.

She shouted for the rest of them.

Two spears flashed from the whirling mists, and then another, and another. Cedrouk stabbed the arm that held Paltik’s wrist. Gart tore the mistfiend’s leg from under it, and it looked back at him with that unmoving, agonized dead face as two more spears crossed through its sides. It died soundlessly, white mist leaking from its empty eyes.

Kez spun, searching for more fiends. She saw none.

Summoning a heavy breeze, she cleared the air around Paltik. The skin about his left wrist and throat looked like dried rheum, peeling and sloughing off where the fiend had grabbed him. He looked at Kez, let out a wet, shuddering cough that made his whole body convulse, and crumpled to the ground.

And there he breathed. Steadily. Alive.

The mists whistled around them in a perfect circle as Kez held her control. The wind was hers, and it was moving.

“Five more?” Paltik wheezed. “We should go back to the shore.”

“Only need four more if you get yourself killed,” Gart said.

If they lingered on the shore too long, the maarozhi would show. They always did. Kez didn’t fancy fighting the dead and sea beasts at once. She shook her head.

Besides, they had done it. She’d done it. Paltik pulled himself along the ground toward the mistfiend, its skin flowing like ink. He wriggled a worn bronze anklet off its foot before pocketing it as proof.

Kez thought about who the mistfiend girl had been. She tried to imagine what Mehrwen’s Stay might have looked like before the mists, or even further back before the storms rose to torment old Pelghain. Would children dare each other to walk out onto the ice flats and come home safe? Would people build houses fearlessly under the sky, unafraid of the deluge and things from the deep?

If she finished her training, if she caught up to her promise, maybe then she could help make it real.

Kez opened her eyes, shaking off the reveries that came so easily here. The mists had curled along the ground as Kez relaxed, and they wheeled around the prisoners’ legs. The valley had seemed calm earlier, but with all the wind she’d called down . . .

“We’re going to higher ground.” Her voice was more frantic than she’d wanted it to be. She yelled at Gart. “Help him. I’ll bring up the rear and shove the mists back.”

“Up the ridge again?” Paltik asked. He was wobbly on his feet.

Mist trickled, falling softly from above. Tiny wisps and flakes now, but soon—

“I’m not carrying him,” Gart shouted, directly at Kez, then looked around at the others. “If you’d like to, have at it!”

Kez was unyielding. “We’re not leaving him behind. Besides, he can still hold a spear. Can’t you, Paltik?”

Paltik nodded. Unsteady. Good enough.

Gart crossed his arms and planted his feet, digging in to waste more time arguing. Then the mists settled atop them both, like a blanket draped over the valley floor, and he vanished from her sight.

Kez twirled her blade to try to save them, carving a tunnel of empty air in the direction of the valley wall, but it wasn’t half as wide as she’d expected. She felt the mists enfolding her, pressing in on her from all sides, with a weight impossible for how they moved.

“Run! The ridge!” she screamed.

She had no chance to see if they made it.

The mists washed over Kez, drowning her in memory

Kez was still yelling after the people she’d lost. They couldn’t hear her over the din.

The waves boomed and the wind roared, and the snarling of the maarozhi cut through it anyway. Two years ago, the unstoppable storms had sent waves smashing into Rag Sound, and the sea beasts rode them onto the islet as it flooded.

Rag Sound’s seawall was not like the glorious edifice shielding Pelghain, festooned in teal and white and decorated by artists and amateurs from every part of the capital. Rag Sound’s seawall was made of the same stuff as its people—leftovers.

But Kez had her orders. When the storm began to pound and rage, Sage Kynon came down from the cavetops, from high dwellings spared the worst of the flooding. He gathered Rag Sound’s handful of bladedancers, Tempests in training, to tell them there would be no help from Pelghain, that they—they—were their home’s last line of defense.

The sage put his charges in two groups—two bladedancers and a half dozen militia volunteers for the stilt homes of her neighborhood, to protect the new arrivals who by bad fortune or bad choice ended up near the coast, away from the safety of the cavetops.

And all the remaining militia and eight bladedancers, Kez included, for the seawall.

Kez swore that they had more than enough to hold the seawall, that the division was a disaster, but the sage brooked no argument. A seawall was Rag Sound’s survival as it was survival for every spit of land in the Cold Isles. And Rag Sound was part of the legacy of imperial Pelghain. And Pelghain was its generations past and future, much more than it was the people living today.

So Kez went to battle, clambered down the swaying miscellany of the seawall, waves smashing all around her, and hewed into the maarozhi until her clothes were black with their blood and her fingernails and most of her sword’s teeth had broken on their scales.

She didn’t fight alone. It likely saved her life. Kez fell more than once, cracked herself head to tail on the wreck of the wall, only to be lifted gently to her feet by summoned wind. Shircan, whom she’d known since girlhood, strode on the tips of her toes across the wreckage, holding a wind edge in her right hand and a practice blade in her left. She needed to wield both blades, like a real Tempest, for balance, she had said.

Shircan died slumped against the wall, with a maarozh tail spine in her throat and a brown line of bile clinging to her chin.

Moon-eyed Izavel sprang between the maarozhi like lightning, her elegant whips of water shearing their limbs free. Until a colossus with the body of a great shark and a ripping lamprey mouth bore her down to the rocks at the seawall’s base and pulled her to pieces in a moment.

Kez wept and fought with her eyes closed for hour-length minutes. She slipped and picked herself up more times than she could count, let the enemy constrict her close so she could tear their underbellies open with wind honed to razors. The seawall did not break, though the monsters ripped at it, though Kez shook with fever and every part of her burned when at last she climbed from the melee.

Scores of wriggling maarozhi bodies lay sticky and gull-eaten along the jagged breakwater. And for the moment, Rag Sound held.

Atop the seawall, Kynon and his retinue watched her climb, and the sage even extended a hand to pull her up, not flinching at the blood. He looked glum but unsurprised, like he hadn’t expected any other outcome. Like he’d paid slightly too much for a nice sattlefish at market.

Kez didn’t waste a second. There was still time, she yelled over the booming storm. They had the seawall in hand. They should divert every soul they could spare to the coast.

“The coast is lost,” Kynon shouted back. “We need you here. Should the storms shift, the maarozhi could rise again and overwhelm us.”

Kynon had picked his choke point, marshaled his forces to it. And decided what he was willing to lose to keep it. So many of her friends and neighbors gone, but the lands of the dying empire endured.

Below them, the hair and cloaks of Rag Sound’s defenders swished lifelessly in the ocean.

For what? It was too much.

“Why send any to the coast? Why not just order the residents to higher ground, rally the defenders here?”

“Focus is your enemy’s most precious resource. And even a single bladedancer can split the focus of the maarozhi.”

There it was. So plain. Spoken as if she were a child.

“You used them.”

“They fought to the best of their ability. They bought us time to defend our greatest asset.”

“You wasted their lives!” She pointed an accusing finger at the sage.

“We are all guilty,” Kynon said.

That was the end of it.

She punched Kynon in the jaw hard enough to knock him to the ground, screaming like an animal while his retinue pulled her back and clamped her in manacles. So began her atonement.

Assaulting a sage should have meant exile. Or death. In Pelghain, there were many creative ways to combine the two. If Kynon thought she was worth killing, he’d have seen her tied to a raft the same day, drifting along the glacial flats near Shiver Cay, covered in offal, with a long, open cut down her belly. She’d spend the night with the seabirds at her entrails and be in a maarozh’s stomach by sunrise.

But he had stuck her in the cage instead. And then let her out. Kynon, the cold fish, thought her life had value. In service to him.

Rag Sound was an isle of wreckage. Inclement and indefensible, a weave rotten to the weft. But Kez had bled for it.

What was any of it for if she didn’t get home?

Kez felt like she’d been punched in the jaw herself.

In the mists, the past bore into now. She’d scrambled halfway up the ridge of Mehrwen’s Stay when she was climbing the seawall in her memories, following screams she could still hear. Screams she knew. She’d moved slower than the Sounders, lost in her reverie. And because of that . . .

The mists weren’t gone this high up, but they were thinner. Freed from their eddying, Kez came back to herself. Her hands were bitten and bruised from grabbing the rocks, but her sword was still at her side.

Kez raced the rest of the way, the wind buoying her every step, carrying her off her feet as she scrabbled from rock to rock and neared the hilltop in minutes. Most of the prisoners’ screams had quieted by then, and she dreaded finding them with lungs full of mist. Another ill-fated battle she’d somehow survived.

She summited the ridge and stood on a mercifully flat outcropping. Mist whirled around her feet. Testing. Not devouring. She would not have to mind it as she had in the valley.

Forms drifted across the hilltop, most trailing smoke behind them. Four mistfiends crowded around Gart. He had slumped to the ground, his arms limp. One fiend’s drifting remnants lay beneath him, but others crouched atop him, fighting to pull the warm breath from his lungs.

Two more fiends encircled Paltik, their fog-tipped fingers pushing into his skin through the earlier wounds he’d suffered. He was struggling to get away from them, but his spear was nowhere to be seen.

Kez sent a quick gust of wind spiraling out to disperse the remaining mist, to see if the fiends would follow it, but they were too intent on their prey.

They had barely defeated a single fiend with everyone standing. Now unarmed Paltik had to deal with two.

Still she would fight with everything she had.

Kez breathed out hard, and the nearest mistfiend, a tall farmer in the remains of a long tunic, broke away from Gart and lunged for her. Kez brought her sword around in a circle, and currents of air trapped the fiend inches from her face. She slashed her blade through it three times, preternaturally quick, and watched the rents she cut in the creature billow white clouds. This fiend had a simple pendant around its neck, and as it staggered Kez cut through the pendant’s cord and yanked it to her. Another proof of death.

She sent flowing air through her sword and directly into the fiend drawing out Gart’s breath, pitching herself forward and slamming into it with the force of a hurricane. Its body withered, swept away by the wheeling mists—but as Kez rose to her feet, the rest of the fiends raked her with taloned fingers, carving chunks from her flesh.

Kez danced back from them before they could drag her to the ground. The rents they’d left on her skin burned icy cold.

Gart’s eyes were open now, but one wheezing mistfiend was still intent on him, and one had raced away from Paltik. It lurched for her with clenching hands, and she hacked it down frantically, vision narrowed to a pinpoint, not seeing another creeping from behind until it rose, tearing at her scalp and neck.

She gasped, first with the pain and then for breath as it tugged at her. Kez leaped away, letting the wind push when her seizing muscles failed to respond. It couldn’t carry her far. Her control was floundering.

Shame and fury battered Kez as she glanced at her comrades. She’d let this happen to them. She had promised, and she was getting them all killed.

Kez swung her sword in an arc with her right hand to keep the fiend searching for an opening. She flung darts of air with her left, aiming for the creature surging around Paltik. It wouldn’t be injured by a meager attack, but it might be distracted—and as the fiend turned from its prey, Kez blasted Paltik with a sweeping wind, tearing him free from its hands and dumping him on his back yards away. She saw him begin to stagger to his feet, and she retreated to the ridgeline as she looked around for Gart, exhausted.

She found him at the tree line. His face was ashen, unsmiling and wan. But he had downed one. He was a fighter. He might—

Sleepy-faced Cedrouk rose up right in front of Kez, fog gouting from his distended jaw. She whipped her sword harmlessly through his empty skull, let the blade fly from her hands, then flipped it back on air the moment he seized her. Cedrouk’s head slipped from his neck, and his body slumped to the ground.

Yet Ponnyd and Silla crept dead-eyed on all fours behind him. The maarozhi were a scourge, but their numbers could be counted. The mistfiends grew in number with each life they took.

As she backed away, Kez’s boots scraped gravel over the ridge.

Who was left to protect? Who had the best chance?

Gart was capable, but mortally wounded. The fiends were swarming Paltik, and he was breathing, but unlikely to slay another. The rest of the prisoners were either still or moving corpses. Kez was standing but ragged, her calls to the wind weakening as her life ebbed. Five fiends dead on the hilltop, yet still more remained. Kez knew they couldn’t win.

They couldn’t win.

The next words in her head came from a living voice, one from her own memory. Focus is your enemy’s most precious resource.

And then: They bought us time to defend our greatest asset.

She hated that voice. But it was right.

Kez drew on every bit of faith and strength she had left. She clutched her blade in both hands, sent a dozen tendrils of wind spinning toward the surviving Sounders.

As Gart struggled to fight off two fiends with a sickly red hole spreading across his chest, the winds cradled him, too weak to lift him to his feet.

But strong enough to knock the air out of his lungs.

As he aspirated, dead Ponnyd and Silla turned from Kez, skeletal noses pointed to the sky, and saw easy prey. Kez stood shivering while the lost Sounders moved to feast.

Their hands closed around Gart’s neck; their supping breaths pulled his life away. The fiends’ hunger stirred, and they drew him down, and mist began to trickle into his mouth as it lolled open.

Paltik gasped madly, taking panicked sips of air that would not come. His frantic eyes searched for Kez, found her, met her by the ridgeline.

He was slumped to the ground, but she heard him over the hissing of the fiends.

“Y-you can’t. Help. Please.”

Kez needed, more than almost anything, to look away.

“Promised.” Paltik huffed the word out, wetly. “Promised.”

She wiped her eyes. She had to focus on the battlefield.

Gart had almost no air left. Suffocating and blue-skinned, he swung his arms spasmodically, croaking at the fiends, at death itself. His words were unintelligible, save the ones Kez knew he meant for her, clear as if he had whispered them into her mind.

“No better than the sages.”

It would take minutes for Paltik and Gart to die. All the while, the fiends of Mehrwen’s Stay came to huddle around them in a drifting circle, easy prey for a bladedancer, even one with a broken sword. The creatures hunched down in satisfaction, their only care a chance to feed.

Kez felt a burn worse than her wounds as she held her breath and kept still, waiting for the battle’s focus to shift. Waiting for her chance.

Her sword was ice cold in her hands, and the mists hugged her close.

Kynon bundled up against the wind, though the wool itched at him fiercely. Most of his retinue remained on the barge, unnerved—though they would never admit it— by the inchoate whispers that seemed to leak from the Stay’s valley. Another hour and they would agitate to leave, with vague concern for his safety as the excuse.

A sage was the death of uncertainty. He had sent the atoners from Rag Sound to kill fiends, and he would not leave without knowledge of their success or failure. So he walked over to the valley’s edge, flanked by two guards, the moment he heard the crunch of sediment beneath boots.

Kez limped from the valley and stood feet from him, unmoving. The guards drew back with their throwing spears, preparing for anything. She looked up at them, wild hair matted down by blood and rain, and her face was unearthly calm, as if it had been frozen still. Though her leathers were rent, she did not shiver, and her lips did not move. She was silent.

Kez had a bundle in her arms. Kynon gestured for the guards to hold their weapons.

He stepped forward and appraised. Gravel clung to her boots where she had walked. No hint of the mists stuck to the whites of her eyes.

Sage Kynon signaled the all clear, and the guards lowered their weapons and turned to shore. Kez walked ahead of them, saying nothing, gait steady as she neared the barge.

She was hot-blooded and arrogant, to be sure. Even after atonement. But such spirit could be tempered, even harnessed. She was also talented and cunning. A survivor.

For years, the great Unmoored, watchers of Pelghain, had warned their sages of a darkness rising to crash upon the isles. It was a danger beyond the deluge and the mists, one that threatened to unmake their home entirely. The Unmoored were no prognosticators; their shifting eyes only looked backward into history. They could not say, or did not know, what form the darkness might take. Only that it was the greatest doom of a nation born to them.

If Kez excelled as a Tempest, she could help find it, endure it—perhaps, one day, even see the dark gone, the storm halted, the empire reborn. And it would be Kynon’s foresight that brought her to the capital.

“What of your atonement?” he asked when she stood a few feet from the barge. “What of the others?”

Kez unfurled the bundle she carried and let the contents clatter out onto the deck of the barge: anklets and chains, pendants and gorgets. Far more than six.

“We are all guilty,” she said.

When Kez boarded, nobody stopped her.